History, Life Cycle, and Transmission

Lyme disease was first recognized in the U.S. in 1975 in Lyme, Connecticut. During this time, a mysterious outbreak of rheumatoid arthritis was spreading in and around the town, affecting mostly children. Two mothers, in desperate need of medical help for their families, reached out to the Connecticut State Department of Health and the Yale School of Medicine. Later that year, a surveillance study led by Dr. Allan Steere and Dr. Stephen Malawista showed that the majority of patients lived in rural wooded areas of town (Elbaum-Garfinkle 2011). Furthermore, in 1983, it was discovered that “Lyme arthritis” (as the disease was initially named) was actually caused by the bite of a tick!

Phase contrast image of Borrelia burgdorferi (Image credit: Brandon Jutras, Yale)

Today, we know that Lyme disease is caused by a spirochete, a type of bacteria that has a characteristic ‘spiral’ shape. The name of the bacterium is Borrelia burgdorferi. In order to infect humans and other mammals, the bacteria must use a reservoir host, which in this case, is the deer tick (Ixodes scapularis). Other species of Borrelia can cause other forms of disease. For instance, Borrelia miyamotoi, which was identified in 1995 in ticks from Japan, is known to cause relapsing fever (CDC 2019). Borrelia mayonii, which was discovered in 2016, was found to cause Lyme disease in Minnesota and Wisconsin, with symptoms that include nausea and vomiting (CDC 2019). For more information on disease transmission and the life cycle of deer ticks, please see the “Tick Ecology” section.

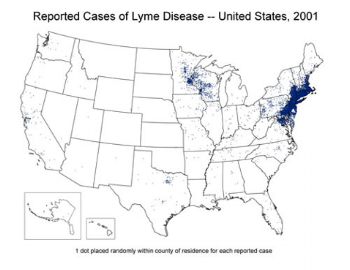

Who Gets Lyme Disease & Where?

About 300,000 new cases of Lyme disease occur annually in the U.S., mostly in the Northeast and Upper Midwest regions. In Wisconsin, Lyme disease is the highest reported tick-borne disease, with the highest number of cases occurring in northern and western regions. The risk of exposure to infected ticks is greatest in the woods and in edge area between lawns and woods. Campers, hikers, and outdoor workers are most likely to be infected, especially in late spring/early summer, when nymphs are most active. Additionally, people who are 5-15 and 45-55 years of age are especially susceptible to Lyme disease (Steere et al. 2016).

Symptoms

Early Lyme disease is marked by erythema migrans, a red circular rash that usually appears at the site of the tick bite within 3-30 days after being bitten. The rash may develop a “bullseye” appearance as it enlarges. The rash is rarely itchy or painful, but may feel warm to the touch. Erythema migrans is the most common symptom of Lyme disease —in fact, it occurs in about 70-80% of infected people (Steere et al. 2016).

Other early symptoms of Lyme disease include:

Source: CDC (click to enlarge)

Fatigue

Chills and fever

Headache

Muscle and joint pain

Swollen lymph nodes

As the disease spreads to other parts of the body, some patients also experience facial palsy (muscle weakness on one side of the face), as well as irregular heart beat or heart palpitations, which are referred to as Lyme carditis.

Late stage symptoms can develop weeks or months after a tick bite and include:

Arthritis with severe joint pain and swelling

Numbness

Nerve pain or paralysis

Meningitis (inflammation of the brain & spinal cord)

Problems with memory or concentration

Sleep disturbances

Diagnosis

Diagnosis usually requires a series of blood tests to detect whether the patient has antibodies to Lyme disease bacteria. However, if the patient has an erythema migrans rash AND lives in a region where Lyme disease is endemic, serological testing is not required. One issue with serological tests is that it can take 4-6 weeks for the body to produce measurable amounts of antibodies (Steere et al. 2016). Therefore, patients who were recently infected may test negative, even though they are infected (false positive result).

Treatment

Antibiotics can be given by mouth, or, in more severe cases, intravenously. Normal treatment involves 2-3 weeks of oral doxycycline or amoxicillin. Persistent symptoms may require an additional course of antibiotic treatment. However, long-term antibiotic therapy is not recommended (Steere et al. 2016).

For information on prevention, please see the “Tick Ecology” section.

Sources

CDC 2018 (“Lyme Disease”): https://www.cdc.gov/lyme/index.html

CDC 2019 (“B. miyamotoi”): https://www.cdc.gov/ticks/miyamotoi.html

CDC 2019 (“Borrelia mayonii”): https://www.cdc.gov/ticks/mayonii.html

Elbaum-Garfinkle 2011 (“Close to Home: A History of Yale and Lyme Disease”): https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3117402/

Steere et al. 2016 (“Lyme Borreliosis”): https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5539539/

For additional reading, please visit the “Resources” tab.